All Rights Reserved by Hasty Pudding

The Hasty Pudding Institute of 1770

The Hasty Pudding Institute of 1770 comprises the Hasty Pudding Club, the Hasty Pudding Theatricals and the Harvard Krokodiloes. Over the last two centuries, it has grown into a premiere performing arts organization, a patron for the arts and comedy, and an advocate for satire and discourse as tools for change worldwide.

A taste of the past and present….

Carters ingenius contributions….

Carter’s reflections on the Pudding shows

(excerps from LOCAL MAN SPOKE WITH JACKIE)

Toward the middle of the spring semester of my freshman year a notice in the Crimson invited prospective writers to come sit in on rehearsals for the 1960 show. I had a problem. I wanted to write the Pudding because it had been the launch pad of major showbiz careers, at the time most notably Alan Jay Lerner of “My Fair Lady” and Jack Lemon. (Not to mention in its 100-plus year history the Pudding alumni who had gone on to greatness in other fields—Franklin D. Roosevelt, who played a young lady, William Randolph Hearst, a germanic valet named “Pretzel” in a show called “Joan of Arc or The Old Maid of New Orleans,” and Edward Streeter, author of the comic novel Father of the Bride which became the movie hit with Spencer Tracy and Elizabeth Taylor.) But the Pudding was a drag show, and I was at a stage where I knew I was homosexual but was hiding it (and some days hoping my homosexuality would just go away). So I went ahead and attended a rehearsal, slinking into the theater in the Pudding clubhouse on Holyoke Street as though I was going to a porn movie.

“Run for the Money,” the 112 th annual production, had something to do with thoroughbred horse racing in Kentucky. The evening I visited they were three or four nights out from their opening, having a run-through with the band in

the pit, scenery and some costumes and lights, but no makeup yet. After the initial shock of the deep-voiced guys in the ringlet wigs shedding their crinolines and high-kicking in bloomers, the drag element began to seem less threatening. The atmosphere was clubby and fairly serious and professional. I couldn’t see how being part of it would necessarily brand you as a homo. And besides, late in the second act a hunky upperclassman came out alone on the stage and reprised a ballad called “Some Love Affair” wearing nothing but a Confederate flag towel-fashion around his waist.

A year and a half later I was chosen to write #114 with the team of Wally Moses and Alan Lutkus, who had composed the music for #113. Though the first Peace Corps volunteers hadn’t yet been chosen, John Kennedy’s brain child was getting a lot of press. What better then than a low farce about a scraggly group of grown-up boyscoutreject types going off to an island in the Pacific populated entirely by sex-hungry girls in grass skirts? Even though I knew eventually the “women” with the flowers behind their ears I was making up would be played by men, the action as I envisioned it kept taking place between “real” men and women. But that was not exactly a problem. The problem was coming up with jokes. In desperation I began writing down even mildly funny things my friends said in the dining hall on napkins and rushing home to insert them into my script.

The annual show was an activity of the Hasty Pudding Club and played the club’s 330-seat theater. The seats were removable—dances were sometimes held in the hall—but the stage, though relatively small, was perfectly equipped in an old-fashioned way with flies to store the scenery drops and curtains and a raked floor (i.e., higher in the back than in the front, so anything dropped on it rolled down toward the footlights). As an organization, the Club was pretty much a mystery to me and the people I hung out with. Harvard had what were called final clubs, the “Porcellian” or “Porc” being the snootiest (FDR again) and some bearing odd animal names like The Owl, or The Fly, or The Fox. Supposedly only bluebloods from upper-class families were ever “punched” for the final clubs, although now several of them were on shaky financial grounds and were accepting the sons of newer money with little regard for the color of their blood. Some clubs occupied handsome brick houses on streets in the range of the campus, others supposedly elegant sets of rooms with business space rented out on the ground floor. (I say “supposedly” because those of us with lesser pedigrees or

no trust fund never penetrated the precincts of the clubs and so had only a vague idea of what went on there. Drinking, it seemed, and raucous parties, fraternity-style orgies? Who knew? Dinners.) The Hasty Pudding, however, was not a final club, but a kind of club for clubbies. Members of the final clubs all apparently belonged to it, brought their girls to the bar and lounge on the second floor and the dining room on the third, but lesser folk could also belong if they had some kind of merit (mostly athletic or, again, parents with money) and were nominated and approved by the Membership Committee. The wider constituency of the Hasty Pudding actually included Jews and several negroes!

The show, I discovered, was a bigger deal than I had thought, the overall budget $25,000, which in 1962 was the price of mounting an off-Broadway musical in New York. The paid professionals jobbed in included the director, the costumer and the scenery designer, and sometimes the orchestra conductor and the arranger. If student musicians couldn’t be found to play in the band for the three weeks in March the show ran in Cambridge, those positions might be hired as well. The show went on the road for a week during spring vacation, with stops sponsored by Harvard alumni in Manhattan and New York’s classier suburbs. But because of the theme of our show—and because all the Harvard big-wigs who had trooped off to join the Kennedy Administration—after the Large Apple we were going to play Baltimore and then close in Washington.

Among those not compensated were the undergrad actors and the writers. In fact, toward the end of the fall Wally Benson, the show’s producer, informed me the writer had to be a member of the Hasty Pudding Club so I would have to join. The fees weren’t that great—three hundred dollars or so?-- but I was furious on principle. I threatened to withdraw my material, thus provoking a flurry of phone calls and a bit of a crisis, which I found enjoyable. The result was that I was given a Pudding athletic scholarship (my one and only athletic scholarship ever).

Before Christmas break, the director they had hired came up from New York for a day. His name was David Tihmar and he had been found by another David--David Rawles--who had worked with him over the summer in musical comedy tent theaters. Tihmar had good credentials. He was a former ballet and Broadway dancer turned director of shows in Las Vegas and for Canadian TV. He also specialized in helping stars and comedians shape their nightclub acts. A dapper, slender man with a sharp nose and red hair (he was only 44, but the hair seemed a little two emphatically red and had not a wisp of gray in it), he possessed a dancer’s wonderfully erect posture and conciseness of movement. He proved both amiable and very efficient. When you made what he perceived to be a joke David would lift his eyes up and laugh as though to fans only he could see in a remote balcony high above your head. In the session with him about the progress of my book and the Moses-Lutkus music, I noticed he portrayed attentive listening with arms crossed and hands at rest, fingers pointed upward, in the way an actor or a dancer trained in mime might. He was very pleased with what he had seen so far, he told us, but he called us ‘you boys’ and said he wanted us to work ‘just like little Trojans’ to be sure we had a finished piece by the time rehearsal started in the beginning of February.

In parting, he put his hand on my shoulder and arched his brow and said, “Now remember, Carter, your job now is write! write! write!”

At the beginning of Spring semester, David Tihmar and I, Alan Lutkus, Wally Benson and David Rawles, who was President of the Hasty Pudding Theatricals (whatever that meant), sat down at a table at the back of the theater full of that glassy expectancy and professional good will you’re supposed to radiate to actors at an audition. Wally Moses accompanied each hopeful on the piano as he sang a song while the rest of us scribbled notes. Someone had clued Tihmar in on how the Pudding worked, but I remained entirely out of it. The fact was the try-outs were fairly rigged and “talent” figured only in some of the lesser casting. Wally Benson, the producer, had considerable experience as a lighting director for more serious dramatic enterprises at Harvard and was able to rope in several accomplished fellows, including the male lead, Peter Gesell, who played a kind of Sargent Shriver character.

But otherwise, it turned out guys who’d been in previous Pudding shows and certain clubbies—especially well-known football players, had an edge. David Tihmar kept glancing over at my notes and then raising his eyebrows just enough to register mild surprise. Finally he confided that I had my criteria all backwards. We didn’t want guys to play the women who were slight or effeminate…our “girls” needed to be tall and brawny with five-o’clock shadow as pronounced as Richard Nixon’s. Then with male characters who were short and wimpy we’d be assured of a laugh every time boy met girl. David also told me, “For the women, we don’t want anyone who seems to want to get in a dress too much, do we?”

The female lead in my show was an older island princess named Mama Twisting Tia Ty-ty (1962 was the second phase of The Twist as a dance craze championed by Chubby Checker). I imagined Mama as a kind of plump, voluptuous Bloody Mary Ethel Waters type. But when it came to casting her, there seemed no doubt in anyone’s else mind that the part belonged to David Rawles, Theatricals President. David’s style was half Tallulah Bankhead, half buzz saw, and he made, as they said of J. Edgar Hoover, “one ugly woman.” It took me a long time to reconcile myself to him as my “Mama.” In fact, it took until I heard the laughs he could wring from the material and the huge applause after he rock and rolled through a second-act number titled “Razzle Dazzle,” (“…a little razzle dazzle goes a long long way”) written especially for him.

David Tihmar began his rehearsals with all thirty cast members walking back and forth across the floor in a line. After a while, he put some rhythm in it, clapping for them, then added in the accompanist on the piano and showed them how to emphasize their walk a little, move their hips.

Then simple lateral movements, cross-overs left and right, then turns, then turns with a lift onto the balls of their feet. He was richly complimentary, expressing his delight with them at all times, and they responded to him. No one claimed he couldn’t do it, and by the end of the first evening David had them all dancing, some fairly well. By the end of the first week, he’d taught the names of steps to the eight or so big guys who would be in his kick-line and had them started on their routine.

I told him what magic I thought he was working, and he turned up toward his imagined balconies and pealed some laughter. Oh no, no, this was easy! he said. These boys were not only athletic, they were so eager and smart. Difficult, according to David, was trying to get a Las Vegas show girl to pay enough attention to learn how to walk down a flight of stairs bearing a candelabra on her head without her tits jiggling in the wind. All those Vegas girls thought about, he said, was hanging out by the pool trying to snare themselves a passing gangster or millionaire.

Stars who fell on their faces because they wouldn’t harken to his advice was a related theme. Bert Parks, the radio and TV “Stop the Music” game show host whose reputation was solidified by many years of hosting the Miss America Pageant, had taken over the title role in “The Music Man” on Broadway after Robert Preston and then Eddie Albert vacated it. Staging a later production for a summer musical theater-in-the-round circuit, David tried explaining to Parks that things would be different with the audience all around him. But Parks had been coached in the role by Morton DaCosta, the original Broadway director, and refused to forsake the blocking he had learned for the proscenium stage for whatever crap it was David Tihmar was proposing. The result, according to David? Disaster!

It is not automatic that a ballet dancer will know how to choreograph, or to block a musical number. But somewhere along the way, David had picked it all up. He was always sure in what he was doing, his work always crisp. The mantra he gave the Pudding actors was “Sell! Sell! Sell!” and even after the show opened and David had gone away it was heartening to stand in the back of the theater on a cold Thursday night and watch them sell…sell..sell!

Throughout rehearsals, he treated the guys portraying male characters entirely straightforwardly. But to get what he wanted from his clubby athlete “females” he often resorted to flirting. Which they seemed to find entirely enjoyable, non-threatening, entirely their due. The “girls” in the kick line—the heart of any Pudding show—wore skimpy bra-tops and grass skirts designed by Theoni V. Aldridge, just then breaking as a hot Broadway costume designer. The number’s big finale placed them down at the front of the stage on their knees. After they’d rehearsed it in the skirts several nights, David stopped everything, came to the footlights and told them, “Now boys, I’ve been informed there has been, um, comment about there being way too much hairy, sweaty crotch in the audience’s face at the finish here. Whoever it is who is objecting is not me, I can tell you, but I do want you to try to see if you can’t get your grass down while you’re going on your knee, I’d appreciate it.” Trilling laughter. “This is Boston, after all! We wouldn’t want the Hasty Pudding raided, now would we?”

When he thought it necessary, he could be foulmouthed. Undergraduates were stationed up on the catwalks above the stage to manage the ropes that rang in and took out various backdrops and curtains. These unsung heroes, there were two or three of them, all younger clubbies, took to drinking as they worked and taking their girlfriends from the local junior colleges up there in the flies to keep them company. At the dress rehearsal, they managed to be late with several cues, and during the notes session after the show, David Tihmar came down on them. “Whatever you gentlemen are doing up there, playing stink finger or whatever it is, you are not paying enough attention to the business at hand!”

His stories about himself were usually tales of triumph, though it was never entirely clear how much of what he said was fabrication, how much hype, and how much real. He had come from Oklahoma, that was definite, and succeeded well enough as a young dancer to get into the Ballet Russe de Montecarlo. He described with great fondness an engagement at the Bellas Artes opera house in Mexico City where he, only 19 (so it would have been 1937) and the ballerina (probably Mia Slavenska) were such a hit in a series of classic pases de deux that they were held over again and again. Poor children with no hope of ever scratching together the price of a ticket would wait for them at the stage door and hand them big leaves with their names picked out in them as souvenirs, David recalled.

And it seemed likely true that he did step into the lead male dance role in “Oklahoma” the second night. (Marc Platt, the original “Dancing Curly” played the opening with a broken foot.) And probable that David was a favorite of Agnes de Mille’s. He had dance appearances in Hollywood movies, brief but real. But had he been the star of the ballet chase with the spectacular leaps in “Brigadoon”? We didn’t know.

His personal life was entirely curtained off from us. During the week, he stayed in a room the Theatricals rented him at a guest house called the Brattle Inn. Rehearsals began in the afternoon and there was a second session at night, but how he wiled away the morning hours was obscure to us. I remember him saying he liked a nice poached egg and tea for breakfast, and that sometimes he did some window-shopping. On weekends he went home to New York, where we knew he had a West Side apartment. But a lover? Personal happiness? Enough money to keep the wolf from the door? We had no clue.

He had worked with the singer-actress Kaye Ballard, who had a success in 1961 in “Carnival,” the musical version of the film “Lili.” One day David told me that the chorus girls in that show dreaded coming off the brightlylit stage into the dark of the wings because they knew the very active hands of Miss Ballard awaited them.

Why share that with me? queer as he was?

Had David intuited I was as

I was so badly closeted that often being in public with him made me uncomfortable. As we got closer to opening, evening rehearsals ran later and later. Sometimes it was after midnight before we closed down, and though we had nothing urgent to discuss, I would go along with David and maybe Wally Benson and a couple of the others half a block up to the “Bick” on the corner at Massachusetts Avenue. Hayes-Bickfords were a chain of Boston cafeterias, the one in Harvard Square no more depressing than any of the others. Brightly lit, with tiled floors scuffed gray by the traverse of years, the “Bick” was open 24 hours and so the refuge of sleepless Harvard students, nodding drunks, vagrants in out of the cold and a large contingent of people who harkened to unseen voices. Late at night the Cambridge cops cruised through with some frequency, either for a coffee regular (which in Boston parlance meant with a good deal of milk) or to bust up a scuffle or a screaming match. From about one in the morning on, there was usually an unnerving, boozy old woman at a small table right inside the glass door. As students came in she would look up and announce loudly, “FUCKIN’ HAHVUD FAGGOTS!”

The food was laid out protected by a glass counter at the back. The “hot” items were kept in steam trays, but by the time the server in his greasy apron slopped whatever it was onto a plate and you trundled it to a table, it retained very little heat. Unappealing as the possibilities were, we chose and consumed anyway.

But David Tihmar in his tailored black pea coat with the big fluffy yellow scarf around his neck was more circumspect. He would waltz up and down the line a few times and finally point to a big plastic bowl containing a kind of citrus and canned fruit soup, and say, “I’ll just have some of that compote.”

“Compote?” growls the server.

David looks surprised, as though the man might not actually be an English speaker as he had thought. “Yes, the compote.”

“One fruit salad,” the server mutters darkly, reaching for a dish.

And I am—briefly—mortified. I look around. Who has seen? (It is a pure case of guilt by association.) No one has seen. No harm has been done. David is tripping along toward our group already seated with his tray and his little “compote.” I recover, and in fact I am ashamed of myself for my disloyalty, for caring what others think about the talented Mr. Tihmar, about me.

Watching something you have imagined come to life—take on a separate, fleshly existence—is an exhilarating experience. I had known in the abstract that the contributions of the various collaborators, starting with the actors, would change what I had written, but I was unprepared for some of the subtle improvements others brought in. The opening scenes of “Peace Decorum” took place in New York. The designer Fran Mahard, a broad-faced, genial and unflappable gentleman from WGBH, the Boston public television station, framed these scenes with what is called a “false proscenium” or outline of the stage picture. Then when the action moved to the tropical paradise of the sex-starved women the “false” frame flew up and out, giving way to a larger black silhouette of jungle leaves and vines. Though an audience might not even notice what had changed, the effect was magical—an enlargement and a deepening of the exoticness of the setting.

But as we neared opening night, I also began to learn some hard truths about how the book for a musical is treated. If David ran short of time during the runthroughs, he took to rehearsing the song and dancing segments and skipping the dialogue. A number would end and he would thumb the pages of the script, saying, “OK, talk talk talk, and now! Places for ‘Who Wants to Learn the Language?’” During technical rehearsals, I noticed that the stage lights were being lowered during dialogue scenes and then cranked up bright again for the musical numbers. Though the effect may have been subtle, I could feel the loss of intensity. When I complained, David assured me that “reading down” the lights during the dialogue was hoary theatrical tradition and couldn’t be changed.

So I began to understand why critics seldom have anything good to say about a musical’s book. The writers never really have a chance. Their contributions to structure and pacing, their ideas for dance sequences and songs and where to put them so they show off to the best advantage? Not a consideration. (Later that year Richard Bissell, he of Say, Darling and “The Pajama Game,” published a book called You Can Always Tell a Harvard Man. Commenting on the 1962 Pudding show the nicest thing he managed to say about me was that I was “no Abe Burrows.”)

(Now, in the 21 st century, a couple of prominent show business people have begun to make the case for considering the book writer’s contribution to the success of the whole. Arthur Laurents does it in a politely self-serving way in his memoir where, among other things, he tags the ideas for songs in “West Side Story” and “Gypsy” which came from him. In Finishing the Hat, Stephen Sondheim is even more emphatic, saying more or less he’d never go anywhere on Broadway without a real dramatic writer along to handle plot and dialogue.)

Our show was virtually pre-sold and so not much dependent on reviews (the Harvard Crimson’s inevitably snotty, the Boston papers’ condescending but sprightly…”these silly Harvard boys having their fun” sort of thing). I loved standing in the back of the theater waiting to hear the house explode over the next laugh penned by me! I missed the performances at the Harvard Club in New York, but rejoined the company for Baltimore and then Washington, D.C., where my family would finally get to see the show on its closing night.

We were hoping for big things. The rumor was that the President and Mrs. Kennedy might attend, although in the end the best we did was Assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Nitze. In the late afternoon, Katherine Graham, owner of the Washington Post, threw us a cocktail party at her huge, beautiful Georgetown home. David Tihmar came down from New York for the occasion.

We were playing Lisner Auditorium on the George Washington University campus, at 1500 seats nearly five times larger than the Pudding theater in Cambridge. “Play big, boys! Big!” David exhorted the cast. “To the back of the house!”

An hour before curtain, Patrick Hayes, Washington’s own “impresario” as he was always called in the papers, came strolling in. Whether he had a Harvard connection I never found out, but as the most regular renter of the auditorium he certainly thought it his right to take charge of the situation. On the Lisner’s broad stage, Fran Mahard’s false proscenium apparently interrupted the view for some of the side seats in the front rows where Mr. Hayes had tickets for his personal friends. So he wanted our false proscenium gone. Wally Benson and I and others went up on the stage and tried to reason with Mr. Hayes. At one point I thought we had him convinced to leave well enough be. But no, at the last moment he turned to the head of the union stage crew and said, “Take it out, Joe,” and the stagehands simply turned, went for the ropes, and flew the offending out.

In spite of a full and mostly appreciative house, the performance went badly, the Pudding boys unable to project into the huge space. I paced the back of the hall feeling sick to my stomach, humiliated, powerless, sad.

Yet another feather in the cap….

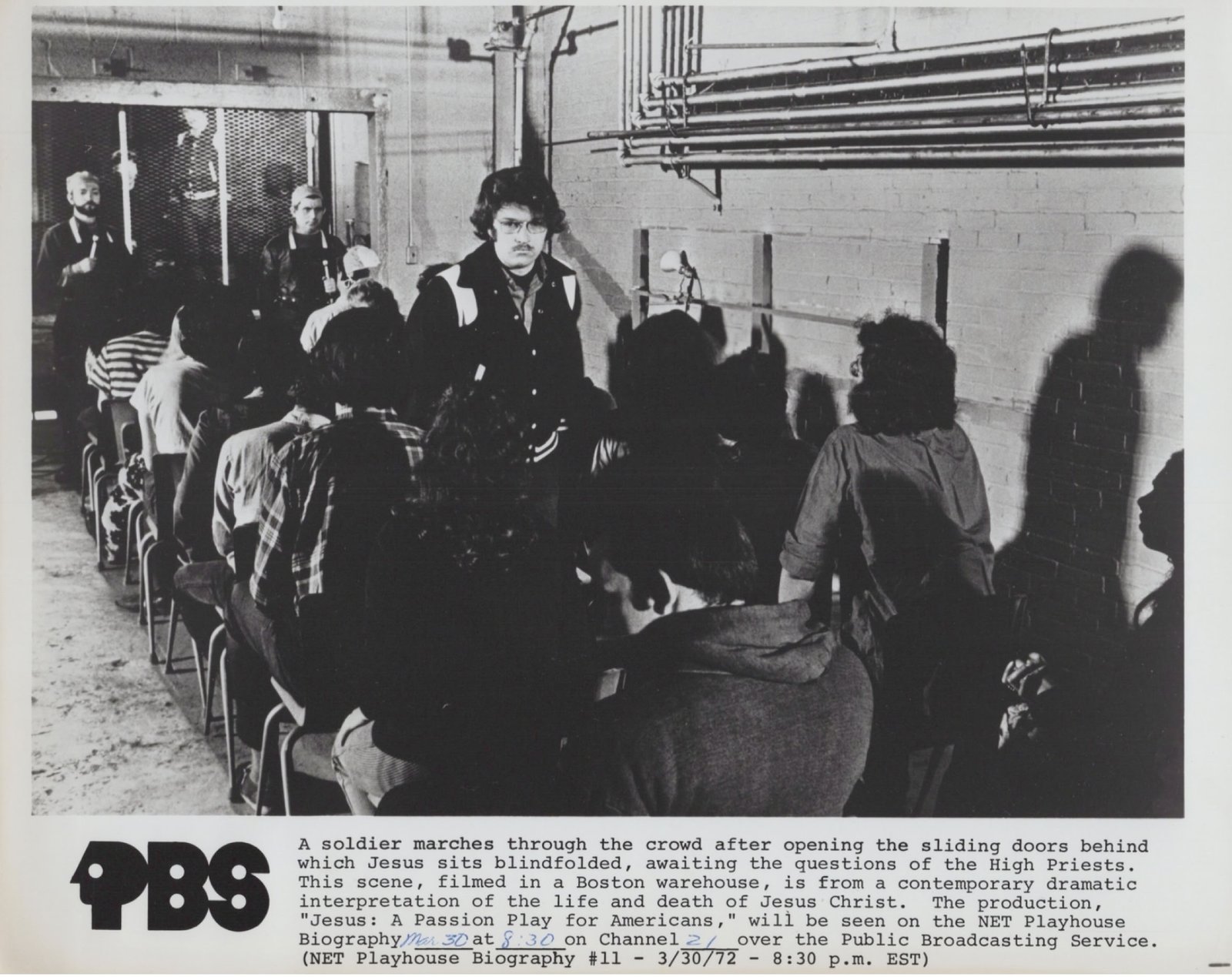

The "Jesus: A Passion Play for Americans" broadcast was a 1972 production aired on NET Playhouse, which was produced through the facilities of WGBH in Boston. This contemporary adaptation of the life and death of Jesus Christ was broadcast as part of the NET Playhouse Biography series.

• Broadcasting Network: National Educational Television (NET) Playhouse

• Year: 1972

• Production Location: WGBH, Boston

• Series: NET Playhouse Biography series

• Content: A contemporary stage and musical production adapting the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

An, of course, there was Teddy…..